To an untrained eye, the artefact looks brown and dull, but it is actually something very special: embroidered wool fabric more than 1000 years old, preserved on top of a turtle brooch.

“Finding embroidered textiles from the Viking Age is so unusual that you almost can’t believe it’s true,” says archaeologist Ruth Iren Øien at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) University Museum.

“Those of us who work with textiles are happy if we find a piece of fabric that’s one cm by one cm. In this case we have an almost 11 cm textile remnant. Unearthing embroidery in addition is completely unique,” Øien said.

In fact, this find was so unique that Øien could hardly believe what she saw through the microscope lens.

“Embroidered textiles from the Viking Age are something we know only from a few opulent graves, like Oseberg and Mammengraven in Denmark,” she says.

Unusual grave

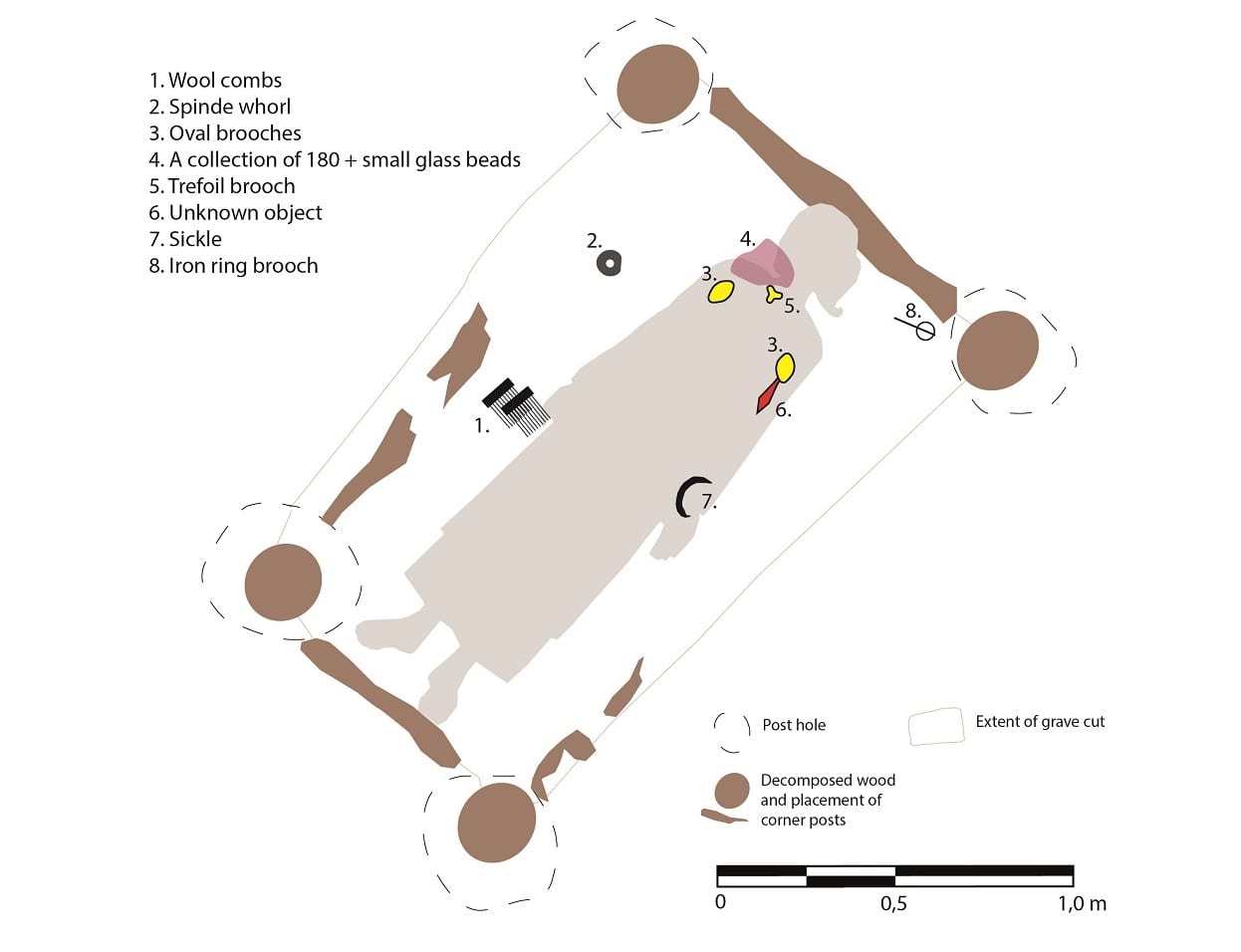

The brooch with the textile was found in a woman’s grave at Hestnes in Norway’s southern Trøndelag county, during excavations in 2020. The grave is dated to approximately 850-950 CE, in the middle of the Viking Age.

The deceased woman was placed in a wooden burial chamber in a long mound above the grave – an elongated burial mound. Chamber graves of this type are unusual in Central Norway.

“Chamber graves are mainly widespread in Birka in Sweden and in former Danish areas – Denmark including Scania (today’s Skåne), south-eastern parts of Norway, and Hedeby in today’s Germany,” says Raymond Sauvage, archaeologist and project manager for the excavation.

The grave goods were also out of the ordinary. The woman was buried with a three-lobed brooch, which is quite a rare find in Norway, typical mostly in the old Danish areas. She was also laid to rest with several hundred miniature pearls – a type known only from a very few Norwegian graves.

“The pearls were concentrated over her right shoulder, but we don’t know if they were a pearl necklace or something else. A find from Hedeby with similar pearls has been interpreted as being pearl embroidery in one form or another, and it’s plausible that the same is the case here,” says Sauvage.

2000 sheep for a sail

Archaeologists believe they have found the remains of eight different textiles in the grave – six pieces of woollen fabric and two of linen fabric. The fabrics vary in quality, structure and appearance.

Today we throw away clothes and buy new ones without thinking twice about it, but that was definitely not the case in Viking times.

“To make enough textiles to clothe a family for a year required a full person-year of working hours. Admittedly, it wasn’t common to get new clothes every year, and a lot was passed down,” says Øien.

Making sails for a Viking age boat required wool from 2000 sheep. Between the labour and raw materials, a Viking-era sail is estimated to be worth between NOK 15 and 20 million at today’s prices.

In other words, the fact that the woman in the chamber grave was adorned with so much clothing means she was buried with items of solid value.

“I would guess that the textiles in the grave were as valuable as the objects she brought with her – if not more so,” says Øien.

Rare insight into woman’s outfit

It is highly unusual to find so many well-preserved textiles in a grave. In several places, the textiles are layered on top of each other, including where the needles attach to the brooches. These probably represent garments from both inner and outer clothing. In addition, several of the fragments reveal information about the stitching and details used for assorted types of clothing.

All this gives archaeologists rare insight into the woman’s attire.

“We imagine that the woman was wearing a pinafore dress, which was fastened with turtle brooches. Under the dress she probably had on a sark or shirt of linen or fine wool. Over her shoulders she was likely wearing a cape with embroidered decorative elements,” Øien says.

“The cape appears to have been lined with a fine wool fabric and along the edge we can see remnants of narrow braiding. This braid might have been made to strengthen the edge, but it also had a decorative function.”

The archaeologists will also take a closer look at the colours of the clothes.

“Under a microscope we can see that some of the embroidery threads have different pigmentation than the fabric underneath. This may be because the types of fibres used in the embroidery threads were affected differently by their time in the soil than the fibres in the fabric. We’re hoping that more analyses will provide us with some answers,” Øien says.

She adds that analysing the colour of prehistoric textiles is extremely challenging, since they were plant-dyed without the use of chemicals. The colours have leached into the ground over the past 1100 years.

“However, some colours are easier to trace than others, like indigo, which creates a blue colour,” says Øien.

Although identifying textile colours can be difficult, it may actually be possible to find out where the wool in one of the textiles comes from. The remnant is so well preserved that archaeologists hope to be able to do an isotope analysis of the fibres.

“Isotopes are variants of the same element, and they vary depending on food sources and between different geographical locations. Analysing the isotopes in wool could therefore tell us whether the fabric came from local sheep or was imported,” says Øien.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)

Header Image Credit : NTNU University Museum